I'm trying to think if there is a precedent for the disaster that was Mitt Romney's little tour abroad -- culminating in a press aide's obscene explosion at the traveling press in Poland on Tuesday -- and it's really hard to come up with anything. Perhaps the closest comparison is his dad George's trip to Vietnam in 1965, which prompted the elder Romney to tell a reporter two years later, as he began running for president, that he'd been "brainwashed" by U.S. generals, thus instantly dooming his candidacy. The consummate irony is not that son may be following father, but that Mitt has spent a good part of his political career trying to avoid the mistakes his father made, as his biographers Michael Kranish and Scott Helman have written.

Which makes the mistakes of Mitt Romney on this trip even more mind-boggling. After the gaffes in London, I really didn't think it was possible that the Romney campaign would let their candidate look foolish in Israel. I even wrote a blog item saying all he had to do was smile for the cameras standing next to his dear friend Bibi Netanyahu in order to come out ahead with the critical Jewish voter bloc -- his real audience -- back home.

And yet the Romney-ites may have managed the nearly impossible task of actually losing Jewish votes on this trip, despite fielding a candidate who has a very close relationship with a popular Israeli prime minister, and who is running against a president whose stand on Israel is one of his chief weaknesses abroad (and with American Jews). The problem was not Romney's tough comments on Iran's nuclear program, which for the most part played well despite some give-and-take between him and his advisor. The problem was Romney's rambling speech at a fundraiser on Monday at which he slandered the Palestinians, completely unnecessarily, and displayed an almost Rick Perry-like obtuseness about the history and politics of the region.

It's not just that Romney oversimplifed historian David Landes's thesis about the importance of culture in economic success, as I wrote yesterday. Or that Romney, the supposed data whiz, got the per capita numbers comparing Israelis and Palestinians wildly wrong. It's that he got the Palestinians so totally wrong. I didn't think it was possible to generate much sympathy among American Jews--moderate, middle-of-the-road ones, that is-- for the Palestinian plight, but Romney seemed to manage to do it when he suggested that"culture makes all the difference" in explaining the "stark difference in economic vitality" between Israelis and Palestinians.

Palestinian spokesman Saeb Erekat retorted that the Israeli occupation is a key reason for Palestinian economic backwardness, and anybody with even a vague idea of Mideast politics, Jew or Gentile, knows this to be true. But Romney's mistake goes even deeper. In truth, the Palestinians historically have had a very vibrant merchant culture, one that is fabled in the Arab world and second only, perhaps, to the Israelis'. So to denigrate their culture, even by implication, is only to show ignorance.

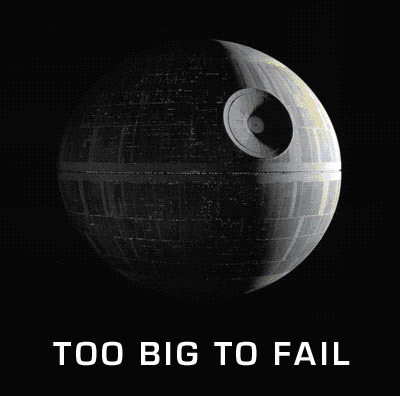

In the end, Mitt Romney's mistakes abroad may not add up to very much in the November election--certainly not anything like what happened to his father's hopes. But if Romney is sometimes described as robotic, he's now looking like a robot who's out of control. Republican functionaries had better start figuring out how to reprogram him -- fast.