This article appeared in the Saturday, September 3, 2011 edition of National Journal.

On Sept. 10, 2001, the United States of America stood at the pinnacle of its power and prestige. Even Rome, in its heyday, did not have the economic and military dominance over rival nations that America possessed. “Nothing has ever existed like this disparity of power,” Paul Kennedy, the historian from Yale (who a decade before had predicted a declining United States) wrote around that time. “The Pax Britannica was run on the cheap. Britain’s army was much smaller than European armies, and even the Royal Navy was equal only to the next two navies—right now all the other navies in the world combined could not dent American maritime supremacy. Charlemagne’s empire was merely western European in its reach. The Roman Empire stretched farther afield, but there was another great empire in Persia, and a larger one in China. There is, therefore, no comparison.”

The United States had a booming economy worth $10 trillion, a budget surplus, some of the strongest capital spending in decades, low unemployment, and little inflation. Its military machine could rain death on anyone from unreachable heights. B-2 pilots could take off from Missouri, bomb Belgrade, and be home for dinner.

If anything, America had grown only more dominant since the end of the Cold War, and perhaps for the first time in its history the nation faced no existential threat. The collapse of the Soviet Union in late December 1991 introduced a promising era of “unipolarity,” and it was soon clear that U.S. power had no rival—even on the horizon. Japan, which only a few years before had been seen as the up-and-coming superpower, fell into deep recession as its “bubble economy” collapsed. Post-Soviet Russia imploded into an economy smaller than Portugal’s. China lumbered forward, a nation in transition, but it remained a developing country with its future as a putative superpower still far off.

Today, things feel almost inverted. The events of Sept. 11 have ultimately left us, 10 years later, with an economy and a strategic stature that no longer seem terribly awesome. America is still the sole superpower, but our invincible military is bogged down in two wasting wars, and poorly armed insurgents seem not to fear us. The rest of the world, beginning with China and Japan, now underwrites our vast indebtedness with barely concealed impatience. We are a nation downgraded by Wall Street, disrespected abroad, and defied even now by al-Qaida, whose leader was killed only recently after spending most of the decade taunting Washington. How did this happen?

Scholars and pundits have offered up a number of explanations in recent years for what they like to call “American decline”: historical inevitability; the rise of the rest. But the most persuasive answer is, in a word, incompetence. The failure of leadership in Washington is so profound that it must rank not only with the worst failures of American presidents, but also with the worst failures of great-power leaders at any time in history—the kind that can turn great powers into lesser ones. “A phenomenon noticeable throughout history regardless of place or period is the pursuit by governments of policies contrary to their own interests,” historian Barbara Tuchman wrote in her 1984 book, The March of Folly, which presented case studies of some of these episodes: Montezuma’s unilateral surrender of his Aztec empire to the Spanish; George III’s bungled handling of the American colonies; the foolish overreaching of America in Vietnam. “We all know, from unending repetitions of Lord Acton’s dictum, that power corrupts,” Tuchman continued. “We are less aware that it breeds folly; that the power to command frequently causes failure to think.”

It is hard to escape the conclusion that al-Qaida outthought America—at least in provoking Washington to make the wrong strategic choices at the outset of the decade. That meant, in particular, all but abandoning the narrower fight in Afghanistan, al-Qaida’s true home, for an unrelated and much larger war in Iraq that we started under false pretenses—which is probably the only way a small, fractious group could elude a superpower for so long. If al-Qaida’s rhetoric is to be believed, one of its main goals was to “bleed” and “bankrupt” America—Osama bin Laden’s own words—through a long and draining conflict, as the fighters did to the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s. “The jihadis expected the United States, like the Soviet Union, to be a clumsy opponent,” Wall StreetJournal reporter Alan Cullison wrote in The Atlantic in September 2004, quoting a remarkable series of letters he found by accident on an old computer left behind by al-Qaida’s then-second-in-command, Ayman Zawahiri, in Afghanistan.

The jihadis were right. America failed, strategically and economically. It failed to anticipate the enormous cost of going into Iraq and of losing focus in Afghanistan. It failed to find a way to pay for the wars that it launched. It failed with its feckless disregard for how all that debt was being amassed in the financial system to pay for war and other expensive government programs, such as the new Medicare prescription-drug benefit. And finally, after all the other reasons for going to war in Iraq had fallen apart—weapons of mass destruction, links between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaida—the final rationale, establishing democracy in Iraq as a model for the Arab world, has proved largely irrelevant as well: The Arab Spring occurred spontaneously, with no known link to events in Iraq.

It has been, in sum, a decade of disaster. The only remaining question now is: How much permanent damage has it done to the United States and its standing in the world?

FIRST BLOOD

There is plenty of blame to go around. Whatever mistakes Barack Obama has made in the last two and a half years, most of the responsibility rests with the chief steward of the post-9/11 decade, George W. Bush. It is no surprise that a survey of more than 230 U.S. historians and political scientists by Siena Research Institute in New York, conducted toward the beginning of every presidency since 1982, now rates the younger Bush as close to the worst president in American history on both foreign policy and the economy. Bush came in at 42nd out of 43 presidents for his handling of foreign policy, just ahead of the dead-last Lyndon Johnson, the main culprit in the Vietnam debacle. He ranked 42nd on the economy, just ahead of Herbert Hoover, who is often blamed for the Great Depression. Since his presidency ended, Bush has also plummeted on other indicators, says Donald Levy, director of the Siena Research Institute: “On imagination, he ranked 40th. On overall ability, he also ranked 40th.”

Levy admits that the scholars who take part in the survey “are somewhat more Democratic than the general population” (and that Bush’s standing may improve over time, perhaps helped by a slew of best-selling, unapologetic memoirs, most recently Dick Cheney’s). But this argument can’t be easily dismissed as partisan. Responsibility for the decade of disaster lies also with the many leading Democrats, including Hillary Rodham Clinton and John Kerry, who supported Bush on Iraq out of a mangled sense of patriotism and apparently because they had few strategic ideas of their own. (“All the intellectual horsepower has been on the Right for the last 15 years,” then-Sen. Joe Biden, who also voted for the Iraq war resolution, lamented to me in 2003, referring to the neoconservatives.) Responsibility lies also with pundits—many of them liberal members of what New York Times Editor Bill Keller once called the “I-can’t-believe-I’m-a-hawk-club”—who became what Bush’s former press secretary, Scott McClellan, later described as “complicit enablers” absorbed in “covering the march to war instead of the necessity of war.” Many in the media have to this day failed to acknowledge their error in public, which has muted any real debate over the choices made during the decade.

Indeed, the bravest and most prescient voices of dissent before the invasion—those who clearly saw the strategic mistake as it was happening—were often Republicans. They were realist hawks anguished by the potential costs in blood and treasure and by the failure to focus on al-Qaida. They were justifiably skeptical of the flimsy evidence that Saddam had WMD or ties to bin Laden’s network. Among them were former National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft, then-Sen. Chuck Hagel, R-Neb., and retired Marine Gen. Anthony Zinni, who in early 2002, while serving as a Bush envoy to the Middle East, spoke against the Iraq war. The Democrats were not without their gutsy dissenters, among them then-Sen. Bob Graham, D-Fla., who as head of the Intelligence Committee opposed the war as a major distraction from the real fight. Graham told me in 2003, “We’ve essentially declared war on Mussolini and allowed Hitler to run free.”

Zinni, a wounded Vietnam veteran denounced as a “traitor” by Pentagon neocon William Luti for his publicly voiced doubts about the Iraq war, now says he feels vindicated. “I still believe it was huge strategic error,” Zinni told National Journal in late August, adding that he would rank the misdirection in the war against al-Qaida among the most catastrophic mistakes ever made by an American president, including those by some of the lowest-rated presidents in history, such as James Buchanan, whose laissez-faire approach to slavery and secession is said to have helped precipitate the Civil War.

The errors against al-Qaida may have been even worse, on balance, according to Zinni. The mistakes made by Buchanan during a national debate over slavery, or by LBJ over Vietnam during the Cold War, came under the pressure of truly existential threats to the union. “This was not an existential threat,” Zinni says. “It was a band of maybe a thousand radicals. Yet we created an investment in this that was on a level of what we do for existential threats. Obviously, we were traumatized by 9/11. I don’t mean to play that down. But this was not communism or fascism.”

This was the first error. The Bush administration convinced itself that terrorism-supporting states were the biggest problem—and that virtually all Islamist terrorist groups, including Hamas and Hezbollah, were equally the enemy. But the problem was al-Qaida, a small, transnational group that had been hounded out of the Arab world into the hands of a lunatic regime in Afghanistan. It had no known ties to any other government, and it could not even agree internally about its goals on the eve of 9/11. “Perhaps one of the most important insights to emerge from [Zawahiri’s] computer is that 9/11 sprang not so much from al-Qaida’s strengths as from its weaknesses. The computer did not reveal any links to Iraq or any other deep-pocketed government,” Cullison wrote. “Amid the group’s penury the members fell to bitter infighting. The blow against the United States was meant to put an end to the internal rivalries, which are manifest in vitriolic memos between Kabul and cells abroad.” Al-Qaida was not a deep organization; it had one A-team and resources enough for one big roll of the dice: 9/11.

For Americans, the attacks of that day were a terrible bolt from the blue, but the initial response—the most natural and obvious of which was to attack al-Qaida’s stubborn host in Afghanistan, the Taliban—only sharpened the sense of American dominance and al-Qaida’s weakness. A devastating air campaign sent the Taliban scurrying from the cities. Afghanistan fell to the Americans and their small proxy force, the Northern Alliance, in just eight weeks.

And bin Laden was all but stopped, right at the outset, when he found himself cornered in his Tora Bora fortress. As Gary Berntsen, the CIA officer in charge of the operation, told me—and repeated in his 2005 book, Jawbreaker—bin Laden said to his followers, “Forgive me,” and he apologized for getting them pinned down by the Americans. (Berntsen’s men were listening on radio.) The al-Qaida leader then asked them to pray. And, lo, a miracle occurred. As Berntsen stewed over the Pentagon’s refusal to rush in more troops to encircle the trapped fighters, bin Laden was allowed to flee. And not only did Bush stop talking about the man he wanted “dead or alive,” the president also began to shift U.S. Special Forces (in particular, the 5th Group, which had built close relations with its Afghan allies) and Predator drones to the Iraq theater.

FALLOUT

That was another strategic misstep. Al-Qaida may have been composed mainly of angry young Arabs, but the group was an organic outgrowth of the anti-Soviet jihad in the mountains of Afghanistan and Pakistan. That region was its home, a giant hideout that required an all-out effort by the international community to pacify. In the months after the Taliban defeat, this was still possible, according to many experts, including key Bush administration officials like Jim Dobbins, the former special envoy to Kabul. The Afghans themselves, in stark contrast to the pent-up Iraqis, were so desperately tired of 23 years of civil war that most welcomed the Western presence with open arms. Virtually every warlord was on sale at knockdown prices. As Ismail Qasimyar, head of the loya jirga, told me when I was there in 2002, war-weary Afghans saw that “a window of opportunity had been opened for them.”

Instead of pacifying the region, the Bush administration, led by former Cold Warriors whose views were shaped by an era of state-on-state conflict, began diverting money and attention to Iraq within weeks of the fall of the Taliban. Only a handful of U.S. troops remained, confined to Kabul. By 2004, Afghanistan had become what Dobbins later described to me as “the most under-resourced nation-building effort in history.” Graham, now retired, agrees. “In February of 2002, I had a briefing at Central Command in Tampa,” the former senator says. “After the briefing, the commander, Tommy Franks, took me aside and said he wanted to talk to me personally. He said in his opinion we had stopped fighting the war against al-Qaida and the Taliban and were getting ready to fight a yet-undeclared war in Iraq. He talked about things like the transfer of military personnel and equipment into Iraq.”

The abrupt shift also disillusioned the neighboring Pakistanis, who had been cooperating; they helped, for instance, to capture 9/11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed in Rawalpindi in March 2003. In an interview in 2004, Mahmud Ali Durrani, then Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States, said that just as Bush was about to invade Iraq, “al-Qaida was almost destroyed in an operational sense. But then al-Qaida got a vacuum in Afghanistan [as U.S. focus wandered]. And they got a motivational area in Iraq. Al-Qaida rejuvenated.”

Chuck Hagel blames the “mad, wild dash into Iraq” on “the lack of any clear strategic critical thinking” about the causes of 9/11. “I think when history is written of this 10-year period, it will record the folly of great-power overreach,” says Hagel, who explains his early stand against the Iraq war as the result of a vow he made to himself as an Army private while fighting the Tet offensive in 1968. “We sent home almost 16,000 body bags that year, and I always thought to myself, ‘If I get through this, if I have the opportunity to influence anyone, I owe it to those guys to never let this happen again to the country,” he says. Not only was there little evidence of WMD (even some Arab leaders like then-Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri of Lebanon thought Saddam was bluffing), but the Iraqi leader was in fact “withering on the vine”; he would likely have been toppled without U.S. intervention, especially by the time the Arab Spring unfolded, Hagel says. “We already had overflights over Iraq and Saudi Arabia. He couldn’t control any of his oil. He had no control of his south. He had no control of his north. He was in trouble. I came to that conclusion in 2002.”

Bush effectively set aside the war of necessity for a war of choice, making precisely the kind of mistake that President Roosevelt avoided in World War II: “In World War II, we didn’t get trapped into side theaters,” says Zinni. Even if it was a legitimate exercise of U.S. power to force the defiant Saddam to surrender his weapons programs—on the chance that he could provide WMD to terrorists—it was a historically reckless act to invade when he had opened up his country to unfettered U.N. inspections after a 15-0 Security Council vote.

Bush invented an entirely new war that both defied world opinion and—in another enormous strategic misconception—gave bin Laden new life by vindicating his often-unheeded warnings to Islamists about the peril of the “far enemy,” the United States. By invading Iraq, Bush displaced Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and other “near” regimes as the bogeyman in the jihadi imagination. “I remember a conversation with [former Egyptian leader] Hosni Mubarak, who said whatever face we wanted to paint on this invasion, the Arab people would see it as an attack on Islam,” Graham says. “By launching this war, we erected enormous billboards of recruitment across the Arab world. People who were essentially moderate became extremists because of what the war in Iraq represented.”

Bush also lost the foreign-policy support of nearly every nation friendly to America, with the possible exception of the United Kingdom. The silver lining of 9/11 had been a wave of international sympathy for the lone superpower. (“We are all Americans,” as Le Monde famously topped its front page after the attacks.) It was a chance to reaffirm the legitimacy of America’s role as trusted overseer of the international system and to unite nations against a transnational threat. It was an opportunity for alliance- and institution-building. Bush squandered it. “The most serious strategic mistake we made is that we turned this into America’s war,” Zinni says. “It was also Berlin, London, Madrid, and Rome that were attacked.”

A LOST DECADE

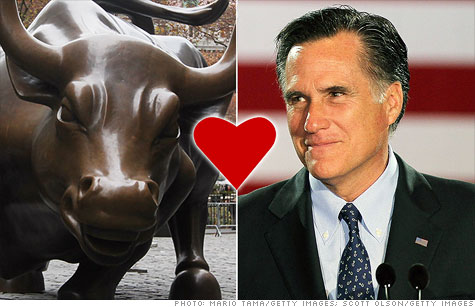

Meanwhile, a series of misguided bipartisan policies began to undermine American economic power. The Bush administration wanted to be the first in U.S. history to pay for wars with tax cuts, not tax increases. Moreover, its commitment to a deregulatory philosophy meant lax oversight of the financial markets. Decisions made in Washington enabled Wall Street to keep inventing new ways to package debt, underwriting Bush’s combination of Bigger Government and Smaller Tax Revenues. But they also helped lead to the credit crisis and the Great Recession. According to Seth Egan of Egan-Jones Ratings, of the $14 trillion or so in U.S. debt, $3 trillion was the result of Bush’s two wars, and $2 trillion came from the credit crisis.

Beyond that, the 2000s became a lost decade. Net job growth was zero, which was unprecedented, especially during wartime. Economic output rose at the slowest rate of any decade since the 1930s. Bottom line: By failing to understand the 9/11 threat, Washington created an expensive, decadelong series of wars that sapped our military, our credibility, our economy, our morale, and our moral standing. It unnecessarily cost tens of thousands of men and women their lives and limbs, alienated much of the world, and distracted Washington from destroying the chief culprit of 9/11.

Furthermore, there is no longer any question that the diversion of U.S. troops—especially intelligence assets and Special Forces—to Iraq produced a resurgence of the Taliban and Qaida movements. Worse, the enemy learned tactics from the insurgents in Iraq. According to Defense Department figures, the number of U.S. service members killed by IEDs in Afghanistan has more than quadrupled in the last few years, rising from 68 in 2008 to 268 last year, while the number of wounded has soared from 270 in 2008 to 3,371 last year. The evidence is now incontrovertible that the failure to complete the job in Afghanistan left us with a quagmire there, while the horrifically expensive Iraq war did not need to be fought.

Bush’s all-embracing solution to terrorism—spreading democracy—was always based on an article of faith, not on a thorough look at the sources of terrorism. Remarkably, the administration never cited a single academic or internal intelligence study linking al-Qaida to a dearth of democracy in the Arab world. True, the Arab Spring this year may be tied to waning support for al-Qaida. (Many young Arabs seem to regard it as yesterday’s movement, and bin Laden’s death appears to have had little resonance.) But considering that the democratic uprisings in countries from Egypt to Syria are occurring independent of our wars, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that the same result could have been achieved with more speed and less sacrifice had the United States adopted a better strategy immediately after Sept. 11. Beyond the damage to the economy and America’s reputation, says Hagel, “look at what we’ve done to our force structure. There are a record number of suicides, record divorces. It’s devastating what we’ve done to our poor [military] people.”

A lost decade does not necessarily mean lost hopes. Graham, one of the few presidential candidates from those years to vote no on the Iraq war resolution of 2002, compares America’s strategic errors with those made during the Peloponnesian war 2,500 years ago, when Athens overestimated its strength and squandered its position in a fruitless fight with Sparta. Afterward, the Spartans dismantled the Athenian empire. Today, America’s rivals—say, the Chinese—aren’t close to doing to Washington what Sparta did to Athens. The United States has an unmatched military and a powerful economy despite dropping back on some fundamentals, such as industrial production and R&D, over the last 10 years, according to the McKinsey Global Institute.

Even disastrous decisions can be undone if the nation honestly assesses its mistakes, Graham says. “I think the lesson to be learned is that it’s the responsibility of American leaders to tell the American people the truth.” That’s not happening yet. “I voted against both Bush tax cuts, against the Iraq war in 2002, and against expansion of Medicare without paying for it in 2004,” he says. “Those decisions most contributed to the debt problem. Yet the people who largely voted for and cheerleaded for those four actions are now saying that the most important thing America faces is its debt problem.”

Despite his low job-approval rating in the polls at home, Obama has already won back some U.S. prestige and allies abroad by taking out bin Laden in early May and his lieutenant Atiyah Abd al-Rahman in late August, and by directing that the U.S. military play a subordinate role to NATO in ousting Libya’s Muammar el-Qaddafi, this time at the behest of the Arab League. “It’s an obvious contrast with the previous administration,” says James Steinberg, Obama’s recently departed deputy secretary of State, who is now dean of the Maxwell School at Syracuse University. But it’s not quite obvious enough. “It’s been a devastating first decade of the 21st century for America,” Hagel says. “We’ll be living with the consequences for a long time.” Perhaps, but the first step toward fixing our mistakes is to acknowledge them. As a nation, we haven’t really done that yet.